On 6th December 2014 Harada Daisuke walked to the ring in a packed Ariake Coliseum to make his sixth defence of the GHC Junior Heavyweight Championship, the second against the man waiting for him in the ring. Leaning across the ropes, he made eye contact with his opponent, fellow Osaka Pro alumnus and the man he’d held Osaka Pro’s tag team belts with on three separate occasions, Kotoge Atsushi. Billed as ‘the Neverending Story’, this match was the meeting of two long-time opponents across two companies – in many ways classic rivals. But the label of ‘rival’ is a heavy one, with grand expectations.

When Harada walked into the arena, he was facing an opponent who could barely acknowledge the ties between them, who repeatedly denied their connection as rivals or as partners. From the moment Harada had joined NOAH in 2013, Kotoge had dismissed their connection. He rejected the suggestion that they were rivals and called the possibility of any tag team reunion ‘boring’. Kotoge’s reasons for this rejection were complex, revealed slowly through hints and stories that exposed the layers of their relationship and the weight behind the label of ‘rival’. But by the end of this match, something important shifted. It was to be a turning point in a long and complex rival story. The story of this match is also the story of how one half of this rivalry, Kotoge Atsushi, came to accept the label of ‘rival’ and, in doing so, laid the foundations for a new partnership.

A meeting of equals?

In its simplest definition, a rivalry is a lasting competitive relationship. In this sense, almost all relationships in wrestling have the potential to be rivalries, as individuals face each other in competition over status and the symbols of success in the form of belts, trophies and tournament titles. However, it is in the repeated competition between equals that many rivalries are built. A seasoned wrestler beating a rookie does not count. There needs to be some parity, often demonstrated through rivals being dojo-mates or from the same ‘generation’; through holding similar positions in a faction or company; or, in many cases, through also being tag partners.

As former tag partners, competing in Osaka Pro Wrestling as Momo no Seishun Tag, Harada and Kotoge, in theory, met the criteria of rivals-as-equals through being teammates. However, their history as competitors up to December 2014 wasn’t exactly one of parity. Kotoge’s rejection of the classification of ‘rivals’ was both a dismissal of Harada as his junior and a comment on his own failure to match Harada’s successes. In many ways, Harada outclassed Kotoge in his achievements. And yet in others, Kotoge, as the elder, was one step ahead.

The GHC Junior Heavyweight title match in December 2014 was the 25th singles meeting of Kotoge and Harada, their 5th in Pro Wrestling NOAH (although they faced each other twice on one day) and only their 2nd for a title. The balance was heavily in Kotoge’s favour, with 15 wins to Harada’s eight and a further two time-limit draws. The count hides a more complex story though, as many of those wins came early in Harada’s career as a rookie.

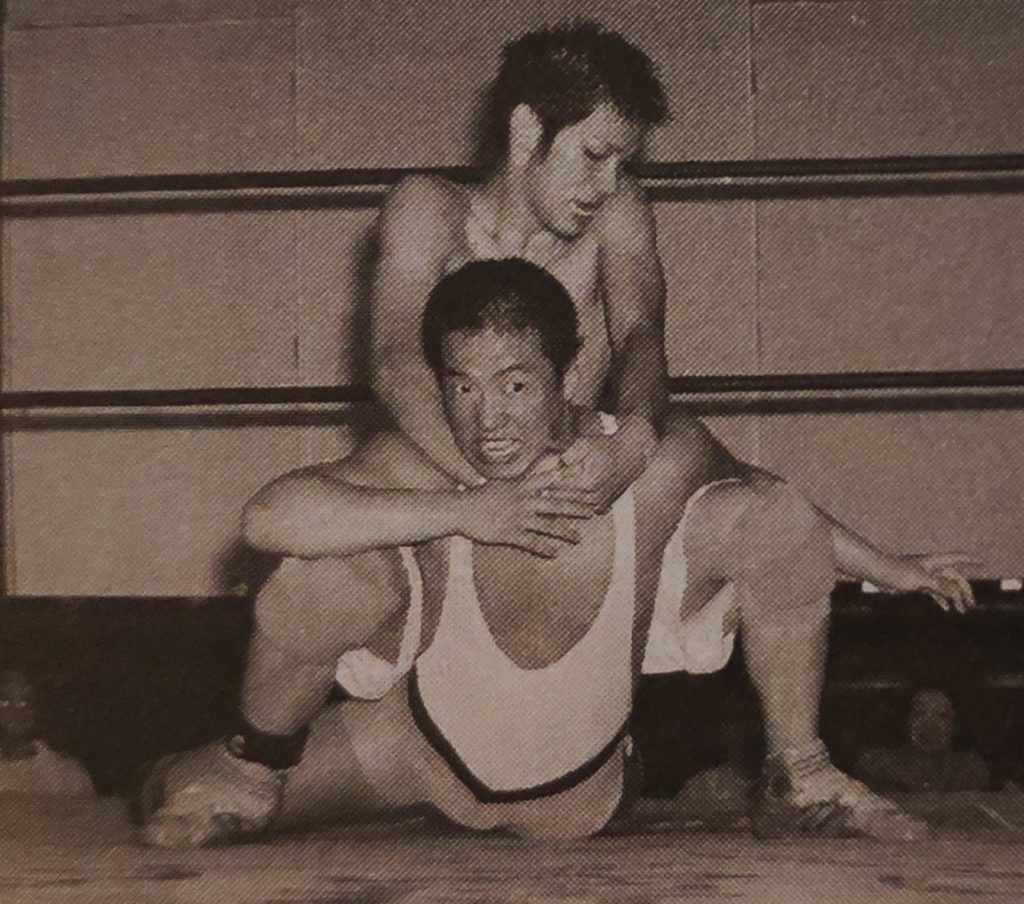

Harada debuted in Osaka Pro wrestling in August 2006, beaten by his senior of 16 months, “the skywalker” Kotoge Atsushi. Already tipped for great things due to his amateur wrestling background, Harada would, like any rookie, nonetheless be beaten by Kotoge repeatedly over the following months. He finally managed to turn the tables in January 2007, getting his first singles victory, naturally over Kotoge, a mere five months after his debut (Kotoge had waited over eight months for his first singles victory). He was not satisfied with the win however, asking Kotoge immediately for a rematch. He was promptly beaten again by Kotoge the following week.

The two gradually became linked as more than senpai-kohai, first as tag partners for the June 2007 Tag Festival and then developing a more formal partnership and making a title challenge in January 2008. The two were also occasional opponents, particularly in tournaments. This is where Harada began to build up his victories. Although it seemed Kotoge could almost always beat Harada in a low stakes singles match, when it really counted, Harada came out on top time and time again. This was the case in Osaka Pro and it had remained the case when the two joined NOAH – Kotoge in 2012 and Harada a year later in 2013. Kotoge beat Harada when the stakes were low and left defeated when it really mattered.

Yet Kotoge was still the senior. Joining NOAH, moving to Tokyo and entering the dojo had put Kotoge in a different world. Whilst Harada was arguably moving to become the ace of Osaka Pro in 2012, Kotoge was competing on a larger stage, getting his first GHC Junior Heavyweight title shot just a month into his NOAH tenure. Within six months, Kotoge had formed a successful tag team with Ishimori Taiji, winning the 2012 Junior Heavyweight Tag League. He had entered the league with Harada in the two previous years, both times failing to advance. When Harada joined NOAH in 2013, almost exactly a year after Kotoge, his first match was a repeat of his very first debut, with Kotoge beating him handily. As Kotoge stood over the collapsed Harada, he gestured with his hands to indicate that he was far, far above Harada’s level. It was a position he maintained, trying to minimise contact with his former partner and avoid comparisons of their positions throughout 2013 and into 2014.

Despite apparently being ahead, Kotoge also showed signs of being regretful about his position in relation to his junior. Though any loss stung, those to Harada seemed particularly significant, and, in the build up to their first GHC Junior Heavyweight title match in April 2014, he acknowledged Harada’s strength as champion and how easily Harada had surpassed him in NOAH. Losing that match, his first title challenge against Harada and held in their native Osaka, was a heavy blow. Although they seemingly bounced back almost immediately to their positions as opponents in rival factions, acknowledging each other as little as possible, their respective positions in the NOAH hierarchy were evident from the title that remained with Harada. Although Kotoge won the Junior Tag titles with Ishimori in July of 2014, they failed to successfully defend them on the first attempt and also suffered a loss to Harada and Quiet Storm in the August Junior Tag League.

By this match for the GHC Junior Heavyweight title, Harada had directly eliminated Kotoge from three tournaments in NOAH and already defeated him once to retain his current title. Despite being a year behind his senior at both NOAH and in Osaka Pro, he held singles titles in both where Kotoge had none. By measure of titles, which really counted in the eyes of Kotoge, he was trailing in Harada’s wake.

The ties that bind

Parity is not the only element on which Kotoge’s rejection of Harada as his rival made some sense. Another aspect of rivalry is its lasting nature. Kotoge’s connections to Harada as a former teammate and fellow Osaka Pro trainee were not links he necessarily welcomed. Partly because of his former partner’s success, these links had the potential to relegate Kotoge to only a supporting role.

When Kotoge had left Osaka Pro in April 2012, he did so having never had a match for OPW’s singles belt. He never won a tournament that brought him close to the title, nor was he a contender, despite his popularity. His place in Osaka Pro was seemingly at the side of his junior, where he played significant supporting roles in some of Harada’s biggest victories. This included the 2011 Tennozan, where Kotoge acted as Harada’s cornerman in a gruelling tournament that earned Harada a title shot and, ultimately, his first singles title in February 2012. This victory by Harada seemed like a moment where Kotoge might finally be able to step up to face his long-time rival and partner, but instead the first defence match went to Black Buffalo, who took the title and seemingly Kotoge’s chance. Kotoge left Osaka Pro just two months later.

Although it seemed there was no apparent bitterness between Harada and Kotoge at the time of his departure from Osaka Pro (in fact their interaction after Kotoge’s final match is possibly the most adorable thing I’ve ever seen), a story emerged in the lead up to their Dec 2014 match which suggested otherwise. Dubbed the ‘Dotonbori incident’, an apparent physical altercation had taken place between the two in the Dotonbori district of Osaka after news about Kotoge’s departure from Osaka Pro was revealed. Harada found out the news at the same time as other members of the company, leading to a conflict that left both feeling wounded – Harada by being left out of the decision, and Kotoge by Harada’s lack of understanding, particularly given that it was Harada’s own success that meant Kotoge’s opportunities in Osaka Pro were narrowing. This contrasts with Harada’s move to NOAH, where Kotoge was apparently one of the first people he consulted.

Kotoge’s decision to join NOAH was a break away from Harada, their tag team, and their rivalry. It represented a chance to find new success, away from the shadow of the younger wrestler he had beaten but not outshone. Harada’s appearance in NOAH almost exactly a year later, prompted partly by trouble in Osaka Pro (Harada was one of several to leave at this time) might have then been a weight to Kotoge who, though very much part of NOAH, had not yet captured that elusive singles title. From the outset, Kotoge seems keen to have put as much distance between him and this anchor from his past as possible.

Rivals in the ring

Despite Kotoge’s protestations, there were some aspects of their relationship he could not deny, one of these being their chemistry in the ring. As Shuukan Pro Wrestling coverage of their December 2014 match remarked, whilst they might not be considered rivals on the basis of their singles record, they were rivals in the ring. Once the two of them were in opposite corners, sparks flew. In Harada’s debut match in NOAH there’s a sense of simple joy as he returns to something familiar. Something that brings the best from them both. The rare moments that they faced off in NOAH in 2013 were equally heated, with seemingly something to prove on both sides.

Although in NOAH they were not partners or teammates, as they had been in Osaka Pro, they seemingly couldn’t help remaining important parts of each others’ stories. A singles match in January 2014, where Harada beat Kotoge, was also the point where Harada announced his intention to join KENTA’s hugely popular No Mercy faction. Harada was a long-time fan of KENTA (when he and Kotoge were booked together for a match at SEM, NOAH’s developmental promotion, Harada had asked for a change to the match configuration so he could face KENTA rather than Marufuji) but he declaration was still a big step, with Harada yet to find a home faction. KENTA gave him a trial match, which Harada lost, but he showed enough to convince KENTA of his petition. Within two months of joining No Mercy, Harada beat Kotoge’s tag partner, Ishimori, for the GHC Junior Heavyweight title, fulfilling his objective in joining the faction. Joining No Mercy was the turning point, but Kotoge was still the axis on which Harada’s story hinged.

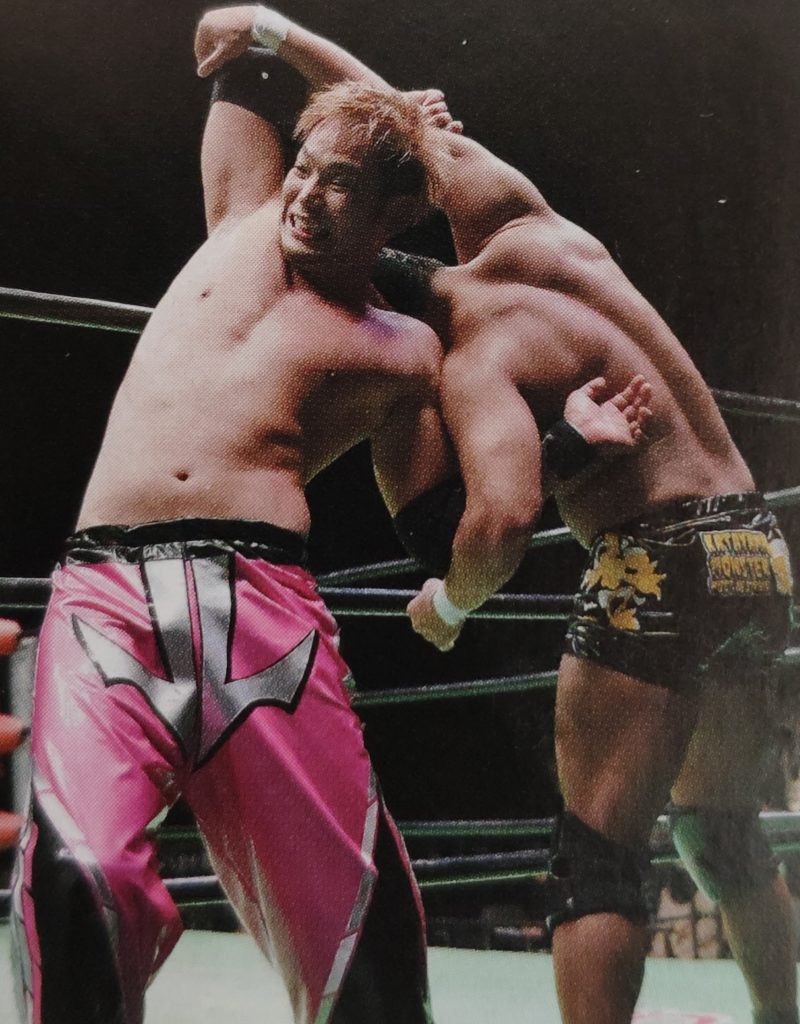

Fittingly then, Kotoge was Harada’s first challenger, facing him in Osaka in a match that was quickly intense and drew on their knowledge of each other as partners and opponents. Prior to the match, Kotoge described it happening as fate, yet there seemed to be little joy in his statement. It seemed more like a resignation to his position than a celebration of their connection. But it was, without doubt, a match of rivals. Pre and post match, in contrast to their previous comments, both were quietly emphatic about the strengths of the other, framing the match as a matter of personal pride. In the match they went to the relatively rare lengths of delivering each others’ finishers, just ten minutes in, but throughout Kotoge’s demeanour was surly, almost resentful that it was Harada he had to face. He fought with a desperation that was different to his previous aggression. Beating Harada was no longer about pushing him away but a desperate need to surpass the man who stood between him and the belt. When Kotoge lost after 18 minutes and multiple near falls on both sides, falling yet again to Harada’s Katayama German Suplex, he had to drag himself from the ring, Harada barely noticing him. The distance between them opened up once again.

December 6th 2014

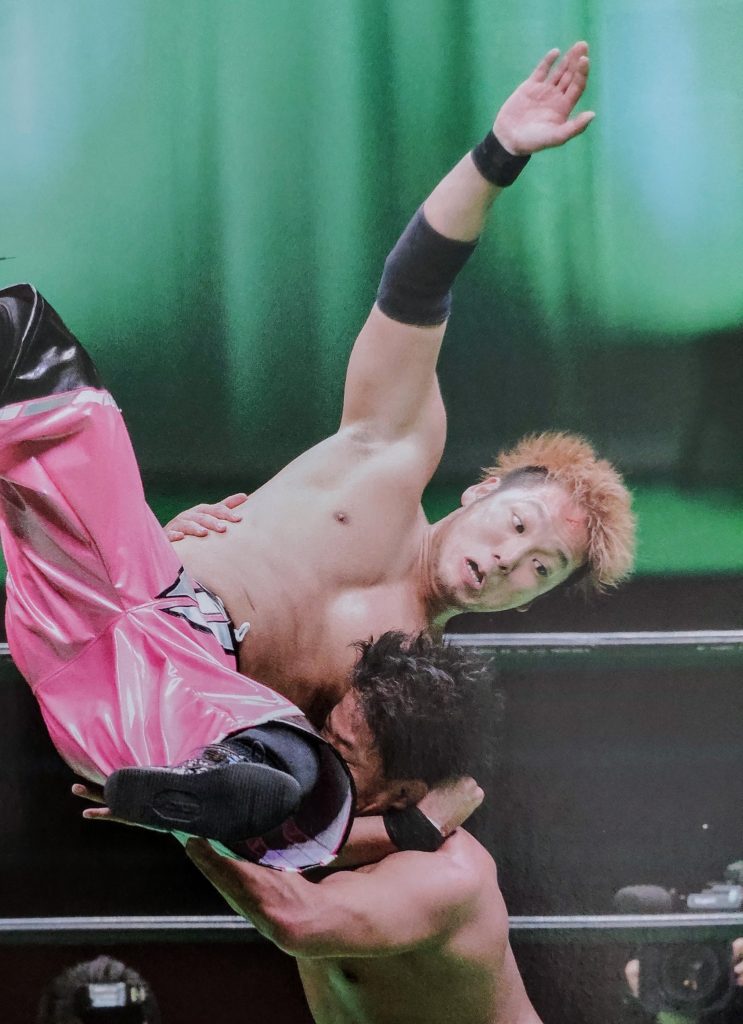

Fast forward to Tokyo, eight months later. The Kotoge who comes out on December 6th 2014 is grinning, cheekily sticking his tongue out at the crowd. Just as last time, this match is a matter of pride, but this time Kotoge does not seem to start from a position where his pride is already wounded. He responds to Harada’s attacks with a calm confidence. Harada is arrogant, quick to assert that his 2-counts must be more and to push his advantage, often to his detriment. Kotoge repeatedly gets the better of him. Harada’s heavier attacks are devastating when they land but Kotoge anticipates them, far more successfully than his former partner anticipates Kotoge. Yet again, there is no doubt that in their skills in the ring, this is a match of rivals.

At some point Harada stops believing he can win. By the time he takes Kotoge’s final Kill Switch he looks dazed and almost confused. There seems nothing he can do to make Kotoge lie down, no blow he can land that Kotoge won’t respond to. The look of dazed confusion and frustration remains as he staggers from the ring, kicking at the barriers as he goes. Kotoge too, looks a little shocked by his victory, deeply emotional as his tag partner Ishimori secures the blue belt around his waist and raises his hand. Finally Kotoge has achieved the thing that separated him from Harada. He is a champion in his own right. Harada cannot hold him back or down.

Kotoge turns to the corner where Harada is still stumbling away to the exit. Looking drained but determined, he walks over to climb the ringpost. It has been a feature of their matches in NOAH that the victor climbs the post to jeer and pose at their departing opponent. Perhaps now Kotoge finally has the opportunity to show Harada that he can beat him when it counts. Kotoge pauses, standing tall, feet balanced on the second rope, hand on hips. He watches Harada make his way to the exit, head bent in defeat. And then he bows. A mark of respect to an equal. A long-time opponent. A rival.

Rivals to…

Harada doesn’t see it. They set a rematch for January. The match is different yet again. A different style. A different mood. Kotoge retains. The match and the result is a big moment. Not only can Kotoge claim another meaningful victory but, in contrast to their last singles match in Osaka where they were fourth on a seven match card, their rivalry takes centre stage as the main event. Even more than that, the build up features Kotoge himself reflecting on their history, not with awkward frustration but with the confidence of a champion facing down a long understood threat. He believes in his own growth. The match cements their rivalry, something finally accepted by both parties.

Kotoge doesn’t get to keep his belt for long. He loses it, painfully, to the invading Suzuki-gun’s Taichi. In August the same year, Harada announces that he and Kotoge are renewing their alliance and tag team. It is clear from the seriousness with which the announcement is made that this is not so much a happy reunion as a necessity brought about by the dominance of Suzuki-gun. But despite these tentative beginnings, the revival of Momo no Seishun tag is a success. They are the first team to take NOAH’s belts back from Suzuki-gun, winning the GHC Junior Tag Team Championships in October 2015. Their partnership even survives Kotoge holding the GHC Junior Heavyweight title a second time and Harada’s unsuccessful title challenge. Distance comes between them yet again at the end of 2016 but not at the cost of their rivalry. The acceptance forced by their December 2014 match remains. Even now, in 2022, deep into the third reunion of Momo no Seishun Tag and relationships that extends to a wider junior team, they appear to enjoy opportunities to still be ‘rivals in the ring’. Long may it continue.